Our investigation into the lives of people living and working along the lower Saco River during the nineteenth century got underway on September 3rd with a trip to the Wood Island Lighthouse. It has long been a vital navigational aid for mariners making their way up the river.

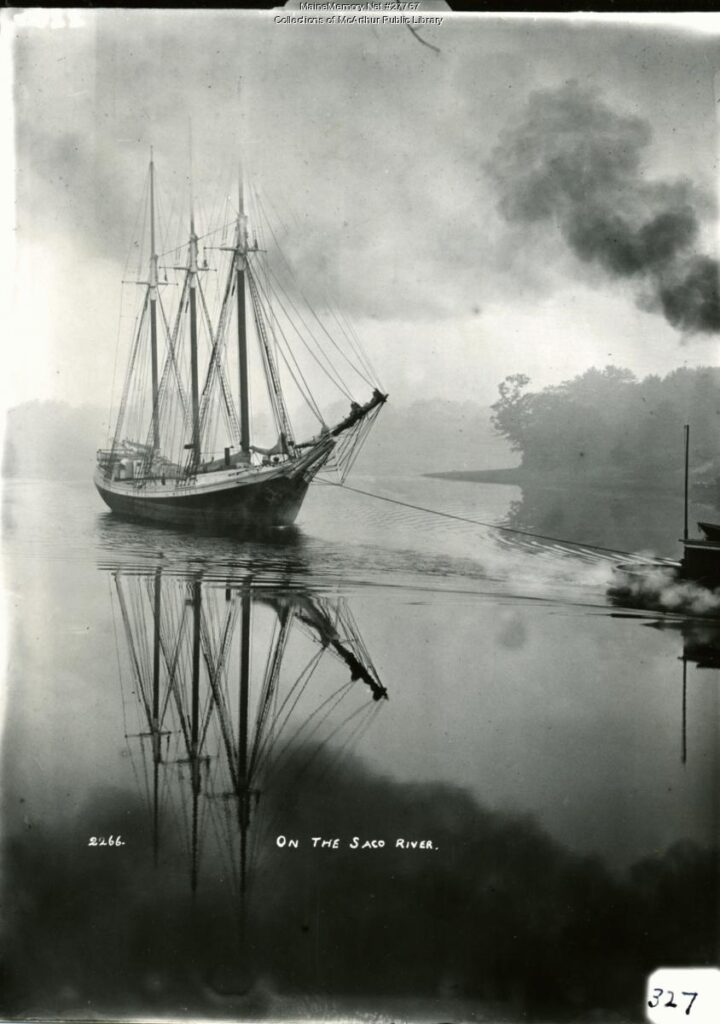

There were a good many such sailors. More than 200 fishermen plied their trade in area waters. By mid-century, regular ferry services catering to a growing tide of summer people and other tourists moved up and down the river and then on to Old Orchard Beach. From the late seventeenth century through the First World War, Biddeford was a shipbuilding center, producing everything from small vessels to three-masted schooners. All of these watercraft needed to find the mouth of the river.

The waters near the river mouth are prone to heavy storms. There are a number of islands, not to mention sandbars and rocks. Until the jetty at Camp Ellis was built, a sandbar hindered access to the river. [Constructing the jetty was not without issue, either. By altering the flow of the river and the positioning of sand, it increased erosion at Camp Ellis to the point that one street per decade falls into the sea. As we learned on our first day of class from physicist Charles Tilburg, if you’d like to retire to this community with waterfront property, buy a house located two or three blocks inland. You’ll be face-to-face with the Gulf of Maine before you can say 401(k). Yikes.] Even a small mishap, mistaking one island for another and turning towards land too early, could result in disaster.

Efforts were taken to mitigate the risk. Congress appropriated funds for construction of a lighthouse on Wood Island in 1806. It opened a year later. In 1825, workers built a navigational tower on neighboring Stage Island (some refer to it as Monument Island). Construction was fraught. The tower collapsed during the building process, killing one man and permanently injuring another.

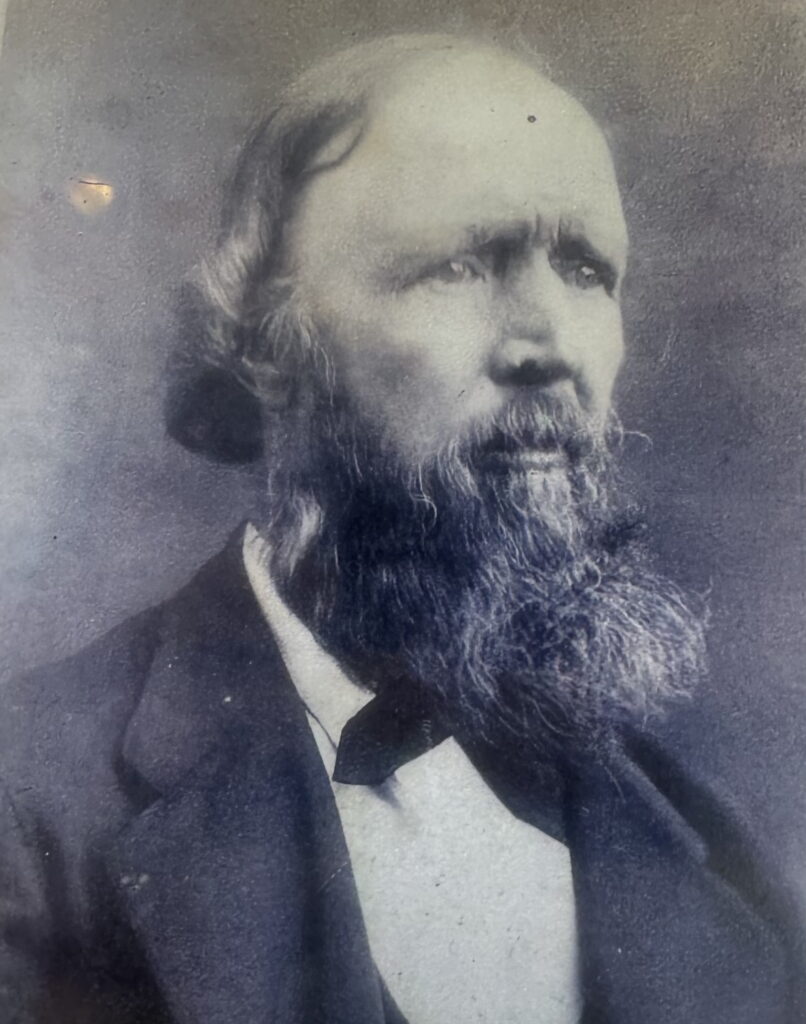

The first keepers of the light at Wood Island got the gig through political patronage: if one supported whoever was in the White House, they had a shot at the job. This isn’t an unimportant detail for us because it gives a sense of early keepers’—most of whom seem to have been local—politics.

There’s quite a lot of information available about the lighthouse and what life was like there at various points in time. Richard Parsons’ wonderful Wood Island Lighthouse: Stories from the Edge of the Sea, for example, is a first rate local history, essential reading for anybody interested in the site.

Our goal was to get a more visceral sense of Wood Island and surrounding waters than is possible through prose. Of course, it would have been different in the past. When the lighthouse was first built, the island was wooded. It got its name for a reason. Then, a combination of storms and farming left the island considerably barer. These days, there are few built structures (where once multiple families farmed), a beautiful boardwalk down the center, and the island is steadily rewilding. As is often the case, the casual observer might be tempted to think it was always like this, with only a few obviously human things marring the wilderness. In reality, the place is very much a product of human/nature interactions.

On the day, we arrived at Vine’s Landing in Biddeford Pool to meet up with our guides, George Bruns and Amy Robinson, and our captains, Mike Massey and Les Smith (who served as crewman on the day). After an orientation, we hopped aboard the Light Runner for the 15-minute trip to the light.

As we sailed, we learned of a recent incident in which a coyote swam out to take up residence on the Light Runner. Animal Control ushered it into the water thinking it would swim to shore, but it instead headed for another boat. Rinse and repeat. Some dogs just feel the call of the ocean more powerfully than others.

We learned more salient information about the islands and the impact of the massive January 2024 storm that hit the Maine coast with remarkable force, damaging the 1867 boathouse on Wood Island, washing massive amounts of stone across part of the island, and reminding everybody just how powerful nature is. In this case, it’s pretty hard not to think about what it must have been like for the keepers when the seas got rough and the winds blew.

Given the nature of the investigation we’ve undertaken, it was quite interesting to learn about the little island that sits between Wood and Stage islands: “Negro Island” (a very marginally more acceptable term than what the people we’re interested in would have used). It’s a tiny thing. Mostly rocks. In the nineteenth century, however, there was a small store sited there. The shop serviced fishermen who found it far easier to drop in for supplies there than going to either the Pool or Biddeford itself.

Once on Wood Island, we trekked along the boardwalk, which George and Amy reminded us is a new addition. Most of the keepers, including all of the ones active during the period we’re concerned with, had to negotiate either the rocks or a muddy track to reach the landing where all supplies came in. It would have been tough.

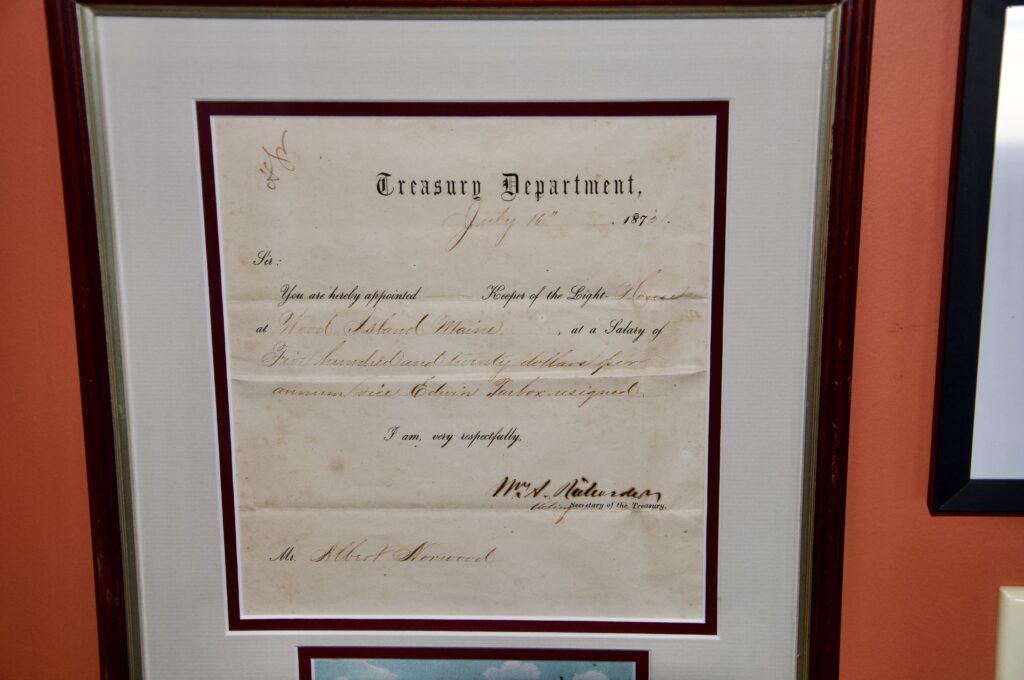

Friends of the Wood Island Lighthouse have done a beautiful job restoring the lighthouse itself. There’s a nice collection of period objects, including Albert Norwood’s appointment papers.

Exploring the house, it was striking to observe just how small the rooms are compared with modern homes. Albert Norwood had twelve kids and there was one fewer bedroom than is there today. It would have been really crowded.

Climbing the more than sixty steep steps up to the light, walking the narrow catwalk, and gazing at the stunning view, it was difficult not to think about what it would have been like in a howling storm. Keepers had to get up in the middle of the night, every night, to attend to the light. A full restful night’s sleep simply wasn’t an option.

The Friends of the Wood Island Lighthouse are hoping to begin rebuilding a barn that Albert Norwood built on the island, a few paces from the house. An archaeological team recently surveyed the site, identified the foundations, and now FOWIL is working to raise funds for construction. Once completed, it will give a sense of the fact that the keepers here had to carve out a living even as they worked to assure safe boat traffic. Maintaining the light did not mean eschewing the life of the farmer fishermen, at least not entirely.

Our exploration completed, we headed back along the boardwalk with a far better sense of what life would have been like for the keepers and their families, as well as what navigating the area might have entailed.

A huge thank you to the Friends of the Wood Island Lighthouse for their hospitality and for sharing the lighthouse with us.

It’s a first-rate tour. If you’re in the area, or plan to visit during the summer, put this on your itinerary. A really grand day out.

Next week, Arthur Anderson will join us for Archaeology 101 in preparation for dig day #1, now just two weeks away.

— Prof. Eric G. E. Zuelow