Our lab is dedicated to understanding and treating the long-term effects of neonatal trauma on the brain and behavior. Most of our work is centered around what might happen to a human infant who spends time in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). These children are more likely to suffer from anxiety, depression and chronic pain later in life. We want to know why and whether we can prevent it. Our research uses a variety of behavioral, pharmacologic, and genetic tools to help us accomplish this.

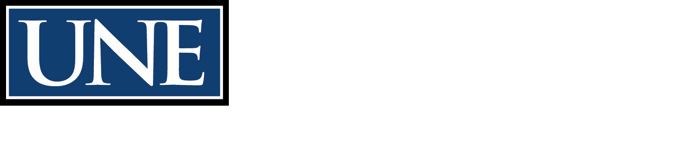

Does Neonatal Trauma Affect Later Pain Sensitivity?

Unfortunately, yes. Our data are very clear, and consistent with other work from the literature, that neonatal pain and stress create a lasting susceptibility to pain. We find that this sensitivity only manifests after a second, later-life, stressor and appears to peak in late childhood or early adolescence.

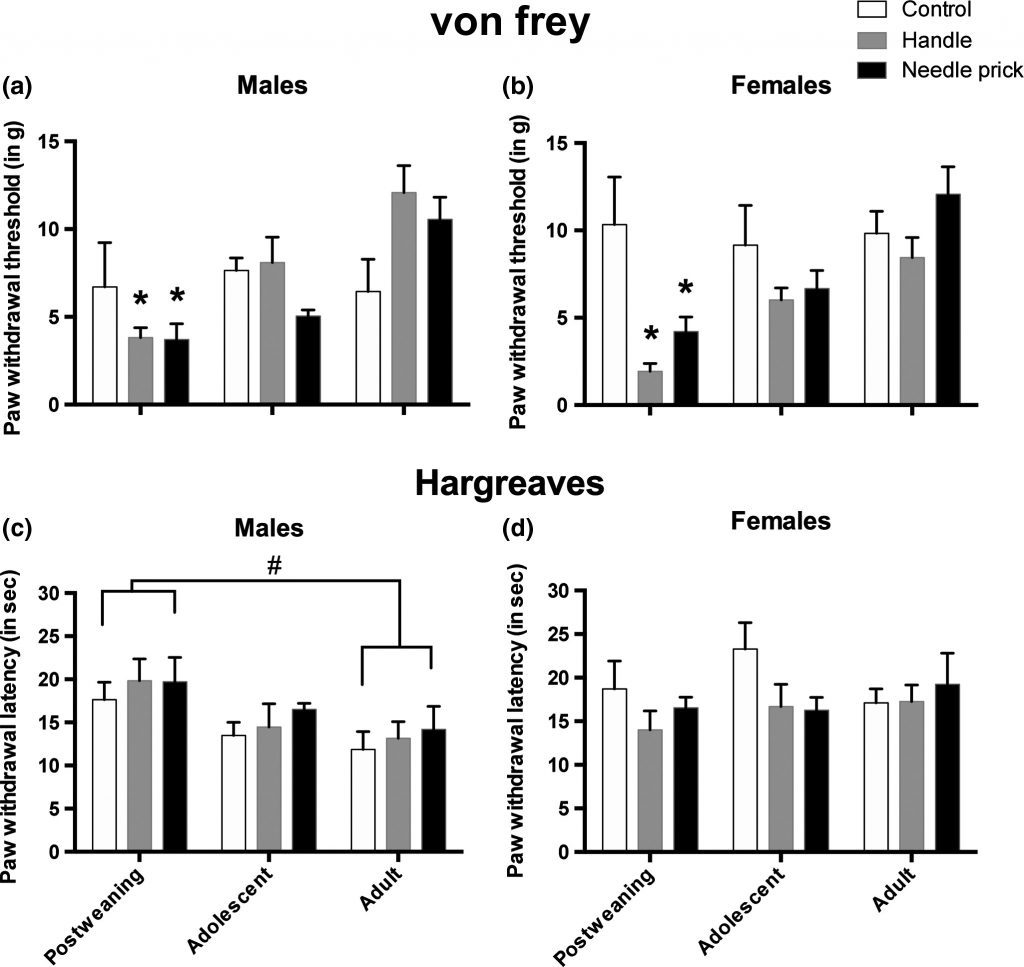

Does Neonatal Trauma Affect Later Fear and Anxiety?

Yes, although here our data are complicated. Our initial findings were that early adolescent fear and anxiety were reduced after neonatal pain. In fact, this has proven remarkably consistent across different types of pain and different measures of fear and anxiety. Does this mean that neonatal pain is good for the infant? We don’t think so. Although some exposure to stress is likely beneficial, we think that what happens after the trauma is critical for the long-term outcome.

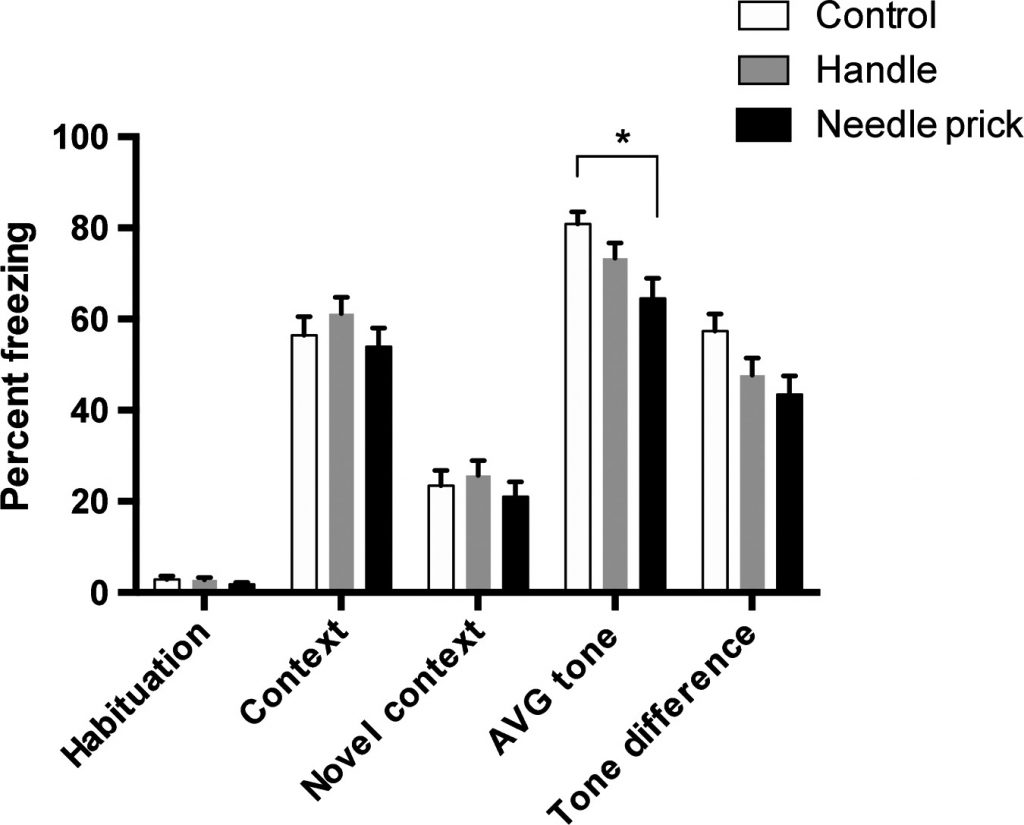

Can Parental Behavior Change the Effects of Neonatal Trauma

So far, the answer appears to be yes! We see significant changes in parental care when the pups are in pain (see below). Moreover, allowing the pups to interact with their mother is essential for later-life reduction in fear. We are in the process of publishing manuscripts showing that keeping the pups away from the mother for a while after a “NICU-like” treatment causes them to be more fearful and anxious later in life.

Can We Identify the Specific Brain Circuits Affected by Neonatal Trauma?

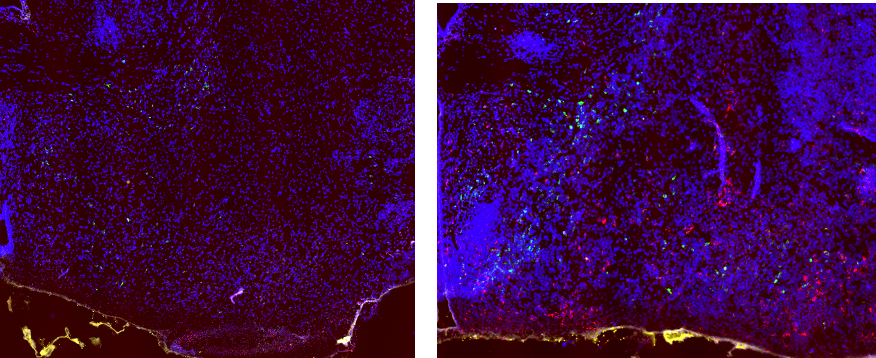

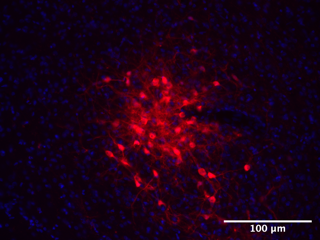

Yes! Interestingly, this appears to be different in male and female rats. Below we have pictures taken from the brains of baby rats exposed to normal rearing or NICU-like experiences. The green is an stress-hormone called CRH. The red is a marker of neuronal activity called c-Fos. You can see that the amygdala region of NICU-exposed subjects is much more active and expresses much for CRH. Interestingly, this is only true in male rats. Female rats are equally affected by NICU exposure, but must have different brain regions involved! We are currently investigating where this is occurring!

Normal Rearing NICU-exposed subjects

Current research questions

We are currently trying to answer three different questions:

- Do CRH-expressing cells in the amygdala change as a result of NICU-experiences.

- Are CRH-expressing cells in the amygdala responsible for the lasting effects of NICU-like experiences.

- What are sex-specific effects of the NICU-like experience.

Mutant Rats! Should I call a Ninja Turtle?

Probably not. We are fortunate to have access to cutting-edge tools, including genetically engineered rats that allow us to visualize and manipulate only the CRF-containing cells. These cells are critical for fear, anxiety and pain and we believe will form the center of a complex circuit mediating the lasting effects of neonatal trauma.

Bibliography

Check out our papers here

Research Funding

We are fortunate to have received funding from the NIH

P20GM103643/P30GM145497 PAINFUL NEONATAL TRAUMA ALTERS SUBSEQUENT FEAR AND SENSORY FUNCTION VIA CHANGES IN AMYGDALAR CRF FUNCTION

R15HD091841 NEONATAL TRAUMA ALTERS SUBSEQUENT FEAR AND SENSORY FUNCTION VIA CHANGES IN LIMBIC CRF AND CORT

Our trainees have also received funding from the Kahn Family Foundation Summer Research Fellowship,