After months of anticipation, the TTNE class finally got their trowels dirty. The Wayside dig is underway!

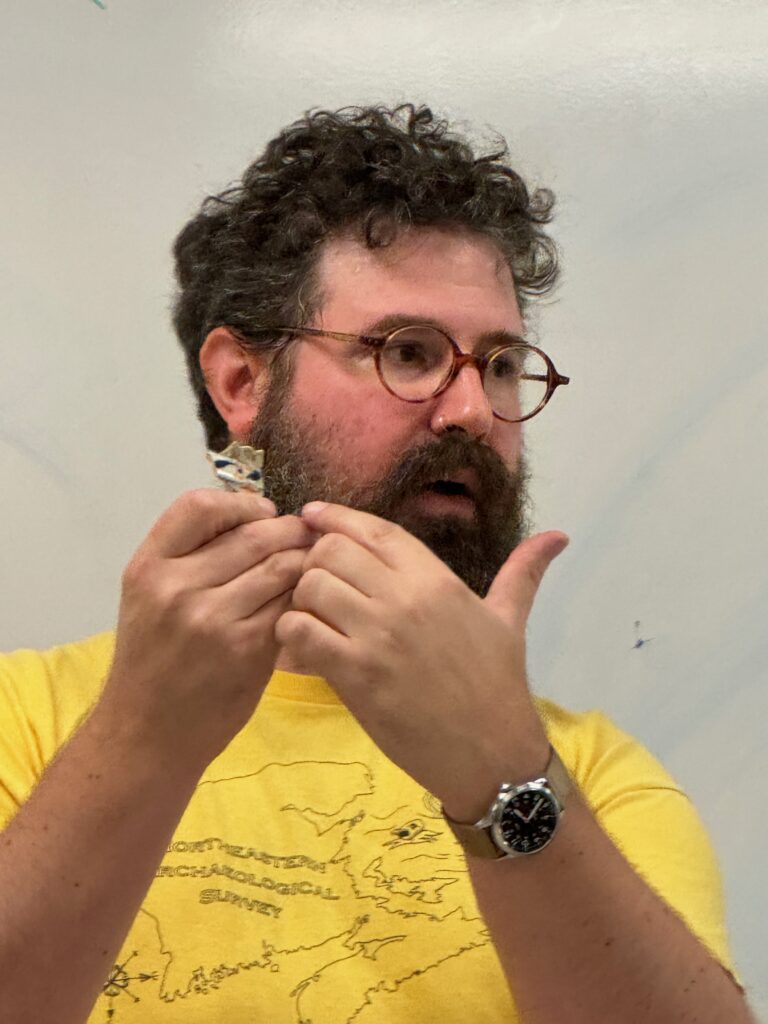

Things started in relaxed fashion. Professor Arthur Anderson, joined by Dawson Burnett (Maine Historic Preservation Commission) who was on hand to help for the day, walked the group through the various types of pottery that they might find in the ground (if we’re lucky).

Pottery, he told the class, is a common and particularly vital means of dating a site.

The idea is simple enough. Archaeological methodology is predicated on “stratigraphy”: as one digs downward, they go back in time. Layer-by-layer. Decade-by-decade.

The challenge is to accurately date the respective layers. That’s where pottery comes in. More recent, mass produced shards of stoneware ought to appear above layers of pearlware, for example. Glazes and designs, not to mention the composition of the pottery itself, make it possible to narrow down date ranges, producing a detailed timeline of habitation that extends downward through 10cm increments of soil.

Or so goes the theory. We’ll see how it pans out in the days and weeks ahead at our site.

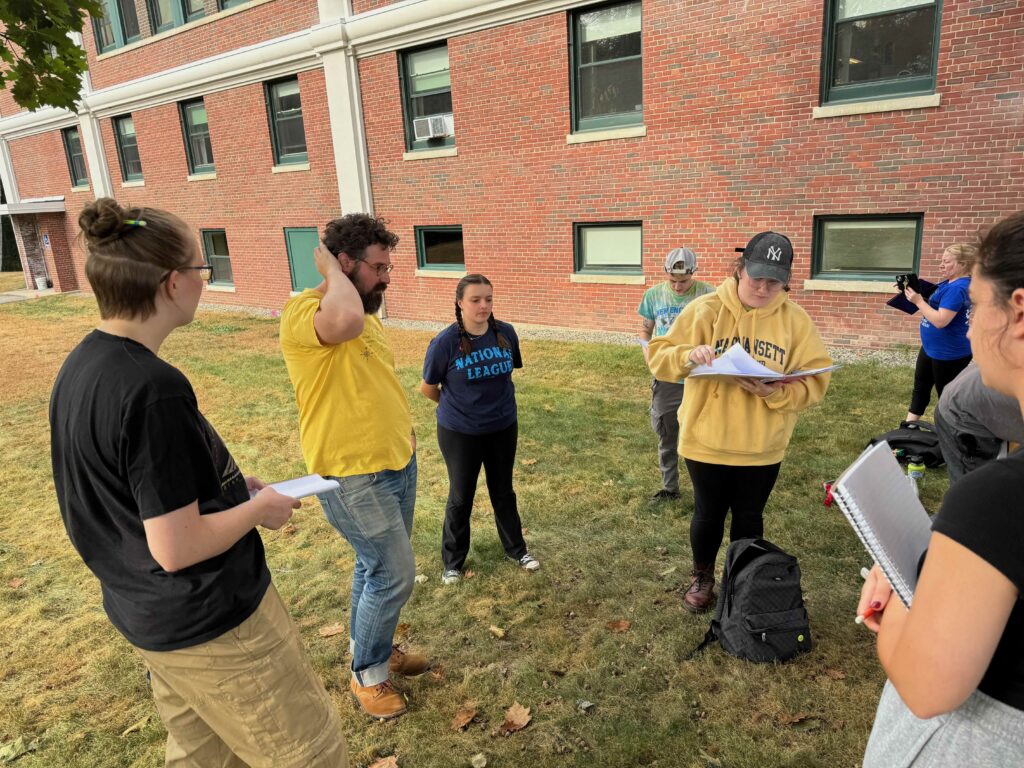

Thoroughly briefed, the class walked to the dig site. In classic Time Team fashion, we discussed strategy. Where should we put in a test pit? Why? How should the pits be oriented?

In our case, the UNE’s Dig Safe team marked not only electrical lines, but also spots where a metal detector announced the unexplained. The obvious thing to do was to simply dig the random flags, but was that really the best strategy?

The class, along with Burnett and Professors Zuelow and Anderson, discussed options. After tense debate and the exposition of conflicting theories, we decided to install our first test pit directly over a flag that was in-line with two others and that appeared to be located where the southern wall of The Wayside ought to be. The spot certainly looked promising.

The second test pit represented a bigger challenge. After some debate, it was decided to put it just north and east of “The Rising Cairn” statue between some other flags. We need a sense of the whole site, not simply flagged locations that may or may not accurately depict the archaeology underground. At this early stage, comparison is our friend.

Trowels at the ready, students began carefully removing the sod which was moved out of the way. When the dig is over, it will slide easily back into place.

Students began measuring 50cm x 50cm squares. Burnett assumed leadership of pit #2, carefully illustrating dig methodology.

At the other side of our site, Prof. Anderson showed the students at pit #1 how to carefully remove soil, bit-by-bit. Once broken free with a trowel, it is carefully scooped into a bucket, taken around the building to our storage and processing site, and sifted through screens in search of any small artifacts.

Some students digging, some watching intently, others hauling buckets for sifting, we all waited to see what we might find. The sod represented a first layer. Nobody expected to find anything in that. The second 10cm layer probably wouldn’t turn up much either. But what was lower down?

For Professors Anderson and Zuelow, tension hung in the air like smoke over a pool table in a shady bar. What if there’s nothing down there? What if bulldozers back in 1963 carried away everything? What if the stratification was so badly damaged by landscaping that the site lacks any integrity at all? What would any of those things mean for our course?

At the same time, and just as in the Time Team television program, it was impossible not to think about very real time limitations. In the original program, the team has “just three days to find out.” We have a semester, but our time is limited to only a few weeks of three-hour days. As each minute ticked by without a find, without even a hint of archaeology, our opportunity to figure out our site was falling away like grains of sound in an hourglass.

But then…. There was a cry from test pit #1. “Glass! We’ve found a piece of glass.” They had. It is small, flat. Window glass. But from when? Crews replaced many of the Decary windows only a few years ago. Had one shattered? There was nothing in the pit to help us with dating.

A few minutes later, a second cry. This time from test pit #2. “Brick!” It’s small. Orange-yellow. Not at all the color of the brick used in Decary Hall. Again, no way to date it in only our first layer of soil and without anything else around to help.

Still, it was something. “I’m feeling good about this,” said Professor Anderson. “This is really promising.”

A few minutes later, another small piece of glass turned up while sifting through soil.

By this point, students had made their way through nearly 10cm of soil and they’d noticed something. It was densely packed. Really hard going with only a trowel to work with. It made progress slow. The clock was ticking.

“We have just one semester to find out…”

Why was it so dense? Had installation of “The Rising Cairn” in 2004 compacted it or was something else afoot?

As the end of class was upon us, Professor Anderson explained how we clean up. Students were told that if they needed to leave, they could. If they wanted to stay a few minutes longer, that’s fine too.

A few held back to finish with a layer of soil while Anderson and Zuelow set about hammering in posts and stringing caution tape. We’d need to wait a week to find out what the third strata would tell.

The remaining students pointed out that the four large spikes marking their test pit were loose. Could they be hammered in a bit more? No problem. Zuelow wacked away at the four nails. Two of them, the one’s furthest from the driveway, went in easily.

The two closest the driveway moved cleanly at first. Down an inch. Two. Three. Then they stopped. Both the same level. 50cm apart. The sound of hammer on spike changed. They’d hit something hard. Stone.

Two large random rocks, both at the same level in the ground? Something else? The wall of a foundation?

We’ll need to wait until next week to find out.

— Prof. Eric G.E. Zuelow